Foreign fighters di rientro in Europa. Sono già qui.

Little is left of the Islamic State’s territorial control, which, at one point, stretched from Aleppo, Syria to Fallujah, Iraq. The intensification of the 60 nation coalition’s effort to defeat the Islamic State has borne fruit, regaining control over key urban strongholds, such as Raqqa and Mosul. Yet, with the degradation of Islamic State territorial control, European nations may face an influx of returnees. The international intelligence and security community has already indicated that, while the IS’s territorial control may cease to exist, it is highly likely that IS as an underground terrorist organization will continue its jihad against Middle-Eastern and Western targets. Not only do they fear that returning fighters have, while in the trenches, adopted the radical anti-Western ideologies of their jihadi peers, but also that they would return to European soil, heavily traumatized and familiar with a wide range of heavy weaponry and explosives. The fact that the 2014 shooting at the Jewish Museum in Brussels, the November 2015 Paris attacks, and the 2016 Brussels bombings involved returned operatives appears to confirm this.

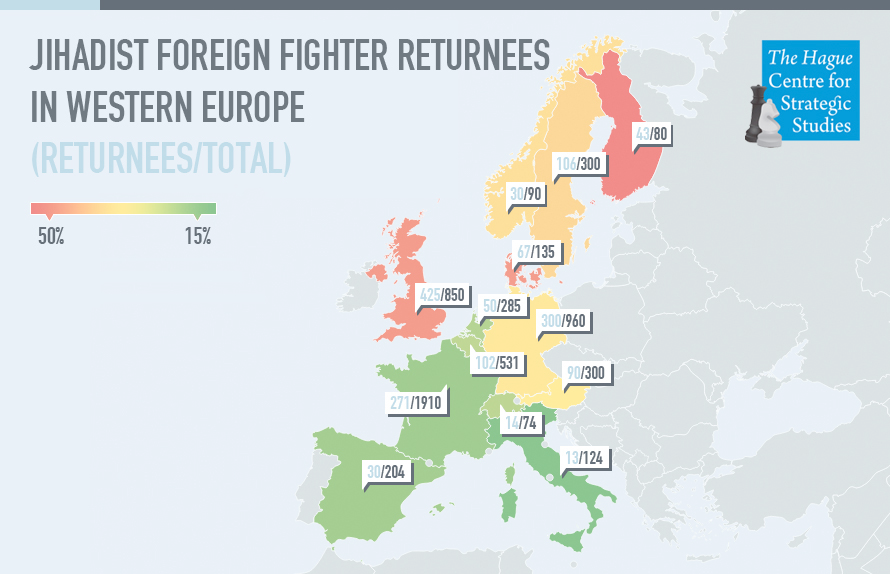

With at least 6,800 European nationals fighting in Syria and Iraq, and estimates suggesting that approximately a quarter – nearly 2,000 – have already returned, the risk is not insignificant. Monitoring these returnees has added significant strain to European intelligence and security services. Closer examination of the available data shows a variance in the number of returnees per country. A (rough) distinction can be made between Northern and Southern European countries (see figure). While countries such as Italy (10.5%, 13/124), France (14.2%, 271/1910), and Spain (14.7%, 30/204) are facing relatively low percentages of returnees, countries such as Denmark (49.6%, 67/135), the United Kingdom (50%; 425/850), and Finland (53.8%; 43/80) have a significantly higher share of jihadi foreign fighters returning. Where does this variance stem from?

First, there is a difference in terms of approach between the mostly Southern European countries on the one hand and the Northern European, especially Scandinavian, countries on the other, with the latter tending to focus much more on the reintegration and rehabilitation of returnees. This soft approach may lower the threshold for disillusioned jihadis that are hoping to return to their home country. In Sweden, authorities have experimented with housing, employment, education, and financial support, with the aim to reintegrate returnees back into society. The Danish so-called ‘Aarhus model’ aims at disengagement, offering returnees a second chance.4 On the other end of this continuum, the prospects of returning to normal life in countries taking a more repressive approach are significantly limited, given the probability of severe penalties upon their return. For example, France, with a significantly lower share of returnees, takes a much more repressive approach, as it is capable of stripping fighters from French nationality, revoking passports, and/or sentencing them to long jail terms. The Pontourny Center, France’s first, and only, deradicalization program closed its doors in August 2017.6 In Italy, administrative deportation of foreign suspects is a common measure: since early 2015, the authorities have deported more than two hundred individuals deemed a threat to national security.

Second, apart from the perspectives upon their return, there is a distinction to be made in terms of national approaches in facilitating return journeys. Danish foreign fighters wishing to return to their home country are actively repatriated, a tactic that fits its inclusive approach. The Netherlands requires its nationals to report to a Dutch embassy or consulate, before they acquire the right to be repatriated. This requirement makes it inherently difficult to return, given the limited possibilities of free and safe travel in Syria and Iraq. Additionally, passports and travelling documents were oftentimes confiscated by IS upon arrival in the Caliphate, or sometimes deliberately burned by the fighters themselves, making travel even more difficult. Other countries simply refuse to repatriate its citizens, as they suggest jihadis should be tried or even killed abroad.

Third, in an attempt to prevent fighters from returning, several countries, including France and the United Kingdom, but also the United States, have formulated a hit list, deliberately targeting their own nationals, aiming to eliminate them and thereby prevent them from returning. Although such extrajudicial killings are obviously far from undisputed, they prefer a dead jihadi over a captured one – a notion that is shared by countries without such a list. Although not all countries have formulated such a hit list, it is possible that these countries provide crucial intelligence that may lead to the targeted assassination of its own nationals. The Netherlands, for example, could provide intelligence to its coalition partners, that may contribute, directly or indirectly, to the targeting process.

Fourth, although there is limited data available on the European level, and the lion share of returnees were part of IS (in Belgium: 64/353; 18.1%), data on the Belgian sample shows that the relative share of returnees who were members of the Al Qaeda-affiliated Jabhat al-Nusra (14/55; 25.5%) seems to be bigger. Although there is no similar data available for the Netherlands, approximately twenty jihadis returned before IS became a player in Syria, potentially implying a similar process at work.This seems to be in line with the general belief that IS tends to be significantly more repressive when it comes to fighters attempting to leave their ranks. (Suspected) defectors are generally considered as spies or traitors, resulting in execution. Hence, a possible explanation for the different numbers of returnees may lie in the different policies of the organization the jihadis have joined. This hypothesis requires further exploration.

So far, a higher share of returnees has not necessarily translated into more terrorist attacks. The 2014 shooting at the Jewish Museum in Brussels, the November 2015 Paris attacks, as well as the 2016 Brussels bombings were conducted by returnees of French and/or Belgian origin. Moreover, the perpetrators of these attacks returned to Europe under the radar of the European intelligence and security community. It is unclear how many jihadis – with or without malicious intent – have returned to Europe beyond the gaze of intelligence and security services. So far, the number of returnees that was involved in terrorist attacks in Europe has been limited. Yet, given their vast number, they represent a significant security challenge for their home countries. Even with the so-called Islamic State collapsed, the conflict in Syria and Iraq has provided a new impetus to global jihadism for years to come.